Twenty-eight minutes.

That’s how long it took from the moment the Japanese torpedo struck the U.S.S. McKean‘s starboard hull until the last of the venerable ship’s four signature stacks disappeared from view beneath Empress Augusta Bay in the early morning hours of November 17, 1943.

For a vessel that had been afloat for a quarter century and had become a workhorse for the Navy and its frequent Marine Corps passengers during the Solomon Islands campaign, the end was swift and tragic.

Of the 338 men aboard, 116 were killed. That the death toll was not even higher was a credit to the coolheadedness of McKean‘s crew, the Marine detachment on board, and the men on nearby U.S. ships who engaged Japanese planes even as they plucked survivors from the water.

In the words of United Press correspondent Frank Tremaine, the “gallant little destroyer-transport … went down with her siren wailing defiance to the Japs and her hull flaming amid a series of heroic exploits which fittingly wound up her 25-year career.”

U.S.S. McKean, circa 1919 (U.S. Navy photo)

McKean had been designed to fight in the Great War, launching on July 4, 1918. But the first global conflict of the 20th century would end before she was commissioned on February 20, 1919. The Wickes-class destroyer, designated DD-90, would make a cruise to Europe in the summer of 1919 but spent most of the next few years patrolling the Atlantic seaboard of the U.S.

She ultimately was decommissioned in 1922, but was resurrected in the summer of 1940 as America grew wary of the looming global threat. As recounted by the Destroyer History Foundation, the Marines wanted a fast transport that could carry landing craft and troops to amphibious assaults. One of McKean‘s contemporaries, the U.S.S. Manley, was successfully converted to that end and McKean soon followed. By August of 1940 she had been redesignated the APD-5 and she was recommissioned in December of that year.

On December 7 of the following year, McKean was in drydock at Norfolk having work done on one of her propellers. But she was back in the water the following day and underway on a training run by the 11th — undoubtedly with a heightened sense of urgency.

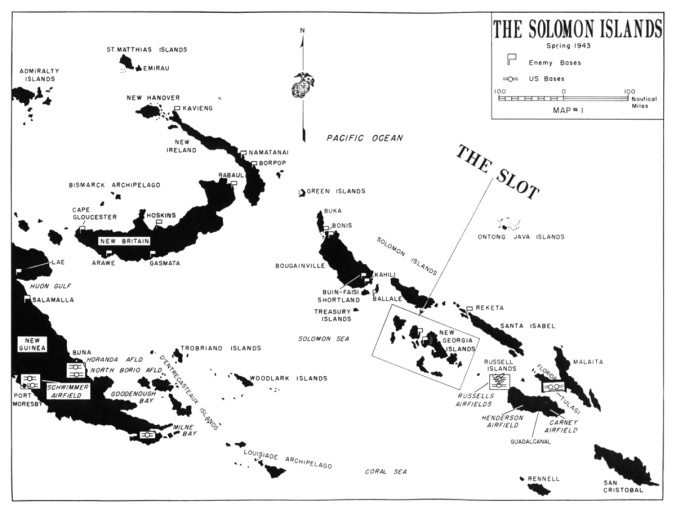

McKean got the call to join the fight in the spring of 1942, transiting the Panama Canal on May 18 on her way to the Pacific. She saw her first action August 7 in the attack on Guadalcanal, delivering Marines from the 1st Raider Battalion to Tulagi. After spending the balance of 1942 running troops and supplies around the Solomon Islands, McKean rotated back to the U.S. for an overhaul before returning to the Solomons in late June. From there, she played a part in landings throughout the region, making regular patrols up “The Slot” from Guadalcanal to the New Georgia island group.

(U.S. Marine Corps map)

Lt. Cmdr. Ralph L. Ramey was in command. A former soccer player at the U.S. Naval Academy (Class of 1935), the Kentuckian had served as McKean‘s executive officer during its 1942 tour.

On November 15, McKean loaded up a detachment of 10 officers and 175 enlisted men from the Third Battalion, 21st Regiment, 3rd Marine Division at Guadalcanal. A task force of 23 ships, including eight LSTs, got underway for Bougainville late that afternoon. The group steamed up the slot without incident, making 8-10 knots, and was within about 20 miles of its destination when the attack began.

Just after 3 a.m. on the 17th, according to the log kept by the U.S.S. Talbot, an unidentified plane dropped a parachute flare about a half-mile behind the convoy. Two minutes later, five twin-engine bombers passed overhead. McKean sounded general quarters at 3:10 a.m., rousing Marines who had taken to sleeping on deck rather than endure the oppressive heat below.

One of them, 2nd Lt. William Kosanovich, told the News Record of North Hills, Pennsylvania, in 1984: “It was close to morning when the battles stations were sounded and that was an awful rumpus. You can’t sleep during battle stations. I was sitting on deck and saw a plane flying past the fantail.”

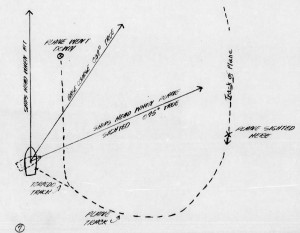

Japanese torpedo planes zoomed through the column, drawing antiaircraft fire from all corners. At around 3:45, McKean‘s crew noticed a plane that appeared to be making a run at Talbot, which was cruising directly to its starboard.

(From U.S.S. McKean action report)

At 3:47, the Mitsubishi G4M1 “Betty” bomber piloted by Gintaro Kobayashi turned sharply to the right and bore in on McKean. Lt. Cmdr. Ramey ordered full left rudder, attempting to present the smallest possible target to the attacker. At 3:49, according to McKean‘s after-action report, Kobayashi released his Type 91 torpedo from about 300 yards. The ship’s crew believed it would pass astern, but it plowed into the starboard side of McKean a minute later, detonating at the after magazine and depth charge stowage and rupturing the fuel oil tanks.

“The entire ship aft of #1 stack was a complete mass of flames,” according to the report. “From the time of the initial explosion it was impossible to go aft of the #1 stack or for anyone aft of that point to get forward.”

The explosion knocked out light and power to the entire ship, and those forward could not raise anyone aft of the detonation site via communications links. Within minutes, the report says, some of the Marines began to jump overboard without awaiting orders to do so. As the crippled ship continued to glide forward, they were pulled into the burning oil pooling around the vessel: “The greater part of the troops that were lost were burned to death in the oil slick.”

Ramey ordered McKean‘s life rafts lowered and crew members and Marines assembled alongside as small explosions rocked the rear portion of the ship. At 4 a.m., she began to sink by the stern and men began loading the rafts. Ramey gave the order to abandon ship two minutes later and the process went off “without delay and without any confusion or panic.”

Ramey and his medical officer, Lt. Jonathon M. Williams, then made one last sweep of the forward areas before going overboard themselves at 4:12 a.m. Six minutes later, the stacks of the U.S.S. McKean disappeared as she sank in 75 fathoms of water.

U.S.S. McKean off Guadalcanal, August 7, 1942 (U.S. Navy photo)

Even before she went down, Talbot and the U.S.S. Sigourney were ordered in to pick up any survivors. Talbot had four landing craft in the water by 4:38 and took on two loads of survivors in the next 40 minutes despite halting operations twice when Japanese planes appeared overhead.

At 5:45 a.m., a Japanese bomber dropped a torpedo on Talbot, but it crossed ahead of the bow and the ship’s antiaircraft guns drove the plane away. By 5:55 the skies had cleared and Talbot had all visible survivors from McKean on board by 6:21. In all, it had rescued 102 Marines and 68 sailors — including Lt. Cmdr. Ramey. One of the sailors, Fireman 2nd Class James C. Evans, died aboard the Talbot due to third-degree burns and “extreme shock” suffered during the incident. Sigourney picked up 15 Marines and 20 sailors, while the U.S.S. Waller took on 11 Marines and three sailors. Waller also took aboard eight Japanese survivors whose planes had been shot down.

Once the crew had time to regroup, Ramey committed his report on the sinking to paper. After the blow-by-blow of the action had been typed up, he praised those on board for their actions in averting an even greater loss of life.

Ramey “witnessed many instances where individuals disregarded their own safety to help some other person who was in danger. Men who were good swimmers agave their life jackets to men who did not have a jacket or were either too tired to swim or were injured. Every assistance was given to the injured. When rescue boats arrived the men that were in good shape refused to have the boat stop or pick them up, sending the boats to where the men were that were seriously hurt.”

In addition, Ramey wrote, “the actions of the U.S.S. Talbot, U.S.S. Sigourney, and U.S.S. Waller during the rescue of survivors is noteworthy due to the fact that they were constantly being attacked by enemy torpedo planes during the time of the rescue. The care and consideration given to survivors by the rescuing ships was greatly appreciated by all hands.”

Despite the heavy loss of life, the majority of the men on board lived to fight another day. Many would distinguish themselves as the war continued, perhaps none more so than their commanding officer.

Ralph L. Ramey in 1935

In February 1944, Ramey assumed command of the U.S.S. McCook, a nearly new Gleaves-class destroyer commissioned the previous spring. McCook arrived in England in late April, just in time for final preparations for the invasion of Europe. Despite taking damage in an air raid on May 28, Ramey and his crew were able to join the armada headed toward Normandy a little over a week later.

By 5:30 a.m. on June 6, McCook was on station 3,200 yards off Vierville-sur-Mer, France. At 5:50, she opened fire on coastal batteries and other targets behind the expanse of sand that would be known from that day forward as Omaha Beach. H-Hour arrived at 6:30, and minutes later the first landing craft hit the beach. D-Day was officially underway, and McCook would play a key supporting role.

Once the troops hit the beaches, naval forces were under orders to cease fire, lest they fall short of their targets and hit their own men. The sailors began to grow anxious around two hours in, as they watched German positions still intact despite air and naval bombardment mow down troops from the ramps of landing craft all the way up the beach.

By about 10:30, Ramey had seen enough. The man nicknamed “Rebel” ordered the McCook toward the beach and swung around 1,300 yards offshore. As Stephen Ambrose described it in his book “D-Day,” Ramey “began blasting away with his 5-inch guns at the Vierville exit, hitting gun positions, pillboxes, buildings, and dug-in cliff positions. Two guns set into the cliff, enfilading the beaches, were particular targets. After almost an hour of shooting, one of the German guns fell off the cliff onto the beach and the other blew up.”

Other ships in the vicinity quickly followed his lead, coming in close to shore and pounding away. It wasn’t long before that fire support helped provide the momentum American troops needed to get off Omaha and establish a foothold in Europe.

I believe my uncle, Paul Newton Frederick, was on this ship at the time the torpedo hit, and was thrown into the ocean. He is still with us as of October 2019.

LikeLike

My uncle Warren Bruce McSwain was also a survivor of the sinking of the McKean. He went on to serve on the newly commissioned USS Smalley till the end of the war. I have my uncles hand written action report of the attack and sinking. As fate would have it he survived the war but was killed in a train vs car accident in Oakland, CA in1948.

LikeLike

I believe my uncle died on this ship. I remember once my Dad mentioning the name.

Is there a list somewhere of those who died when the ship was sunk?

LikeLike

Hi Kimberly — you can find a partial list here: https://www.wrecksite.eu/peopleView.aspx?RtW3JgvuIjU6n4e3oHBTYA==

Looks like more detailed information is available via Fold3.com, but you have to pay for a subscription (or use a free trial if you haven’t already)

LikeLike

Hi Mark, Ralph L. Ramey was my Uncle Rebel. My father, Simon Everett Ramey, was a graduate of the USNA Class of 1937. Another older brother, John William Ramey, was also a USNA graduate. I do not know what year Uncle Bill graduated, his birth date is 8/22/08. All three of these men were orphans, as was their older brother, Palmer T. Ramey.

Thank you for writing this interesting and historical article.

Charlotte Ramey O’Connor

LikeLike